A request this morning reminded me of this book. I say it is one of my favorites because I recommend it a few times each year. It is from the Wild Plants in Flower series with photographs by Torkel Korling and essay and species notes by Robert O. Petty – longtime biology professor here at Wabash College. My favorite is Volume III The Deciduous Forest. Maybe this is because these are the plants that I know best; the flowers from the woods of my childhood. The excellent photography of Mr. Korling is still, all of these many years later (the book was published in 1974), just as fresh as ever. But I think the real reason that I like it so very much is because of the essays and species notes by Bob Petty.

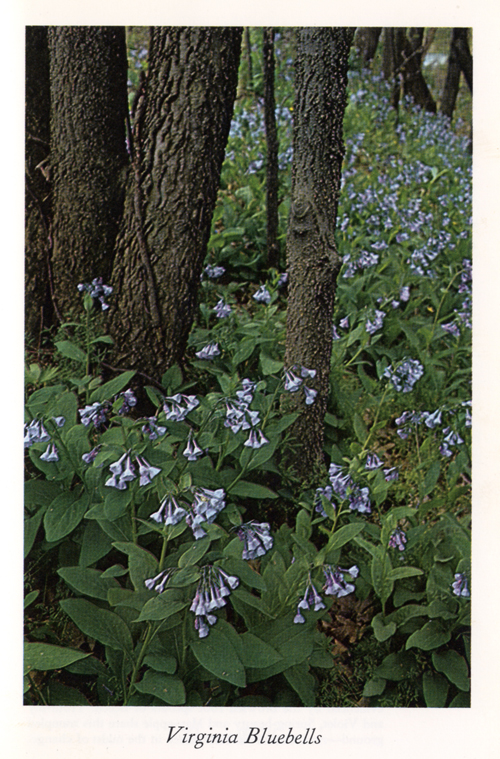

I believe it was taken in the woods at my home over three decades ago. Bluebell Valley, we call it, and it is just a gorgeous little valley when completely covered with these lovely blue flowers. A sure sign that summer is on its way. Yet, as the weather is cooling here I think about the end of this book, “By October, the forest is burning amber and crimson in the brief evening light. There is a sharp and pungent sweetness to the air – the smell of walnuts. The nights are cold.” A sudden wind drifts storms of yellow leaves and tumbles fruits and seeds. A night rain breaks the last dead leaves away from ash and maple. The walnut trees are long since bare – the last to get their leaves, the first to lose them. Here and there in the dry oak woods, a clatter of acorns breaks the stillness. The youngest oak and beech trees wear their dead, russet foliage into winter.” The wild flowers are only a rumor now. The plants are dormant. All the ancient strategies are one.” Really a lovely book and as I return to it each spring I wonder…was Petty a biologist with poetry in him or a poet who studied biology?

Best,

Beth Swift

Archivist

Wabash College

One comment on “My Favorite Little Book”

Beth, Thanks for the Bob Petty memories. One of my prized possessions is an autographed copy of this book. I have fond memories digging trees from the woods at his home and transporting them to campus we we did the initial plantings for the “Petty Patch” together.

Bruce Terrey Class of ’78

Bruce,

I am so glad you enjoyed this post…the Petty Patch is just a wonderful little island in the arboretum.

Beth

Comments are closed.