Just recently I had a visit from a young scholar, a fourth grader from a local school working on an Indiana history project. She wanted material and information about Caleb Mills. As I prepared for her visit, Mills kept popping up in other work. So I have been thinking a lot about Caleb Mills and thought perhaps our time might be well spent if we could obtain a better picture of the man. Pull away the preconceptions and really look at the man and his life’s work.

Now we all know a little something about Mills – even if it is only that he had a bell. This bell greets you as you enter Wabash as a freshman and it rings for you as you leave at Commencement in one of the neatest traditions in education.

Beyond the bell, if pushed further you might say that he was the first teacher hired by Wabash. But how many know that he is referred to as the “Father of the Indiana school system?” I didn’t. But having heard this and years ago reading that he was the second superintendent of Indiana schools made me wonder how he could be the father of the system? Seemed a reasonable question and the answer is a perfect example of Caleb Mills as an activist. Let’s talk about Caleb Mills not as some old figure head in our history, who happened to be the first teacher with a neat bell.

Instead, I want to introduce you to Caleb Mills Man of Action. I will share with you several instances of Mills as a man with a lifelong passion to do good work. He was a man on a mission to make a difference in the lives of those around him, his students certainly, but also to improve the lot of his fellow citizens. A man who believed that education was the key to a good life and a right of all citizens.

Caleb Mills was indeed the first member of the Wabash faculty, hired in the summer of 1833 as the only teacher at the Crawfordsville Classical High School, which would grow into Wabash College. Mills was a graduate of Dartmouth and Andover Seminary, like his friend and former roommate Edmund O. Hovey – a founder of Wabash College. Mills, like Hovey, worked for the American Home Missionary Society and had a passion to do good work in the West. In fact, Mills had worked in this area for a time before he returned to Andover to finish his seminary training.

In January of 1833, the Prudential Board of Wabash, forerunners of our Board of Trustees, advertised for a teacher in the pages of the home missionary society newspaper. They were looking for a man who could teach during the week and serve as minister to a church on Sundays. This one man could, they said, “Do more to benefit the country than three ordinary missionaries.” Mills applied for the post adding that Hovey knew him and his qualifications. By July, Mills was nominated as teacher and Hovey wrote to Mills offering him the post. With hindsight we can see that the words of that ad were prophetic. Caleb Mills WAS that one man and his life’s work was even greater than the ad supposed.

Mills arrived in Indiana in November of 1833 in miserably cold, wet weather with his new bride, Sarah. Accompanying them were her sister, Lydia Marshall and a missionary teacher, Salina Wyatt. Forest Hall was still under construction. Mills’ new job was to teach ALL of the classes and on December 3, 1833 he began by calling the students together with a humble school bell.

For his teaching at the school he received the student’s tuition. Remember there were only twelve students at first and tuition averaged $5 per term. To supplement this meager amount the American Home Missionary Society paid him a small salary in exchange for serving as the minister to a local church.

Mills taught five days a week and on the sixth he went out to his church – described as six miles west of town. He spent Saturday evenings with his church people, stayed overnight, delivered a sermon on Sunday and returned home. In summary, he worked seven days a week for very little money. Later in his life he reflected that he was paid least when he worked most. Mills was motivated, not by money, but by a passion to improve the lives of as many people as possible.

Preachers and teachers is a sort of a shorthand phrase we use to describe the motivations of the founders of Wabash. They were interested in educating those who would educate and minister to the thousands of illiterate Hoosiers then filling up the Wabash Country. Mills wanted to teach so that good, highly qualified teachers could go out from Wabash and deliver high quality education to their pupils. In turn these teachers would bring the light of learning to the members of their communities. It was this, above all else, that drove Mills.

To understand the needs of the country, let’s look at the state of education in Indiana in the middle 1800’s. There were schools scattered around the state, but they were all merely local ventures which is to say sporadically funded – really barely funded – and operated for short periods of time. Just a few weeks each year, not uncommonly coinciding with breaks from the colleges when teachers [students at college] could be hired on the cheap. Instruction was limited and often of poor quality, as there were no standards for teachers.

Of more importance to Mills was the fact that these schools were subscription schools, meaning they were only open to those who could pay tuition. Thus insuring that those with the most need of an education, the poorest of our state, were the least likely to receive it.

To better show the need for education, let’s look at the numbers from the 1840 census. 1 of 7 Indiana adults could not read or write, not even their name. This placed Indiana dead last of all northern states in terms of literacy.

By late 1846 Mills decided to take DIRECT action. He took up his pen and wrote a piece entitled, “An Address to the Legislature.” He had this piece printed in the Indiana State Journal which was on every legislator’s desk at the opening of the General Assembly in Indianapolis. The anonymous letter was full of passion, vigor and statistics and signed “One of the People.”

The numbers I cited above come from Mills’ address to the legislature. We have in the Archives the very copy of the 1840 census he used when composing this plea for universal FREE education as a means of raising the living standard in Indiana. He was determined to bring this issue to the attention of as many legislators and citizens as possible.

It is likely that Mills was driven to action by a committee formed earlier that year which noted that only 37% of school age children attended school and that those who did were only there for a few weeks each year.

In this first address, Mills noted that the only public money allotted to schools came from the federal government. There was 640 acres of land per township set aside that could be sold to fund a school. The problem with this is that, first of all, that’s very little in terms of the need for a building, books, supplies AND a teacher year after year. Also, land in the poorest parts of the state was worth a good bit less and the students in those communities, Mills thought, were the ones who most needed education.

In all, Mills wrote six addresses between 1846 and 1851. It is widely accepted that it was his work that drove the legislature to create a true public school system. These addresses were not simply pleas for funds, nor were they attacks of high minded rhetoric, although they contained both. They were so effective, in the end, because they provided a clear-eyed assessment of the problem – AND more importantly – they provided simple, straight forward solutions.

As the addresses continued through the years Mills applauded the positive steps taken, offered his views on needs unmet and ways to continue the improvements. He included possible sources of revenue, boards for governance and ways to fund libraries in each community school.

In fact, in 1850, as legislators gathered to write a “new” constitution, there appeared in the Indiana Statesman a series of four letters by One of the People. Again, here is Mills bringing his message to the people and their legislators at just the right moment. His aim in these four messages was to have the education laws enshrined in the constitution where they would be safe from tinkering or future reversals.

Mills was not simply an editorial writer. He also had each message privately printed, at his own cost. Each message carried the subtitle “Read, Circulate and Discuss.” Mills sent them all over the state. The evidence is that his readers followed this direction and they were widely circulated and extensively discussed.

His last address as One of the People was in 1851 as the General Assembly went to work under the new constitution. Mills wrote of the importance of any new laws as a reflection of intent. He said that any laws passed must contain state supervision of common schools, competent teachers AND standards for them. More importantly, Mills felt that the freedom to function outside of politics was essential.

The laws created and passed in 1852 contained funding in the form of taxes equally distributed to all areas of the state, local control which was subject to review by the State Board of Education, which was then watched by an elected state Superintendent of Public Schools. In short, a system of checks and balances Mills thought essential for decent statewide education.

In his book A History of Education in Indiana author Richard Boone says of Caleb Mills, “Among all those who saw the calamitous ignorance of the people, and who were ambitious of better things for the state…was one whose contributions were sufficiently definite and sound to be recognized as the chief factor in its solution.” Boone P.91

So now we understand why Mills is called the father of Indiana education. It is for his steadfast determination that the more people that were educated, the better it was for all of Indiana.

Mills was elected State Superintendent of Public Instruction in 1854 and took a leave of absence from Wabash to do it. While in this position he visited every county in the state and addressed students and voters at every chance. His Address to the Youth of Indiana is a classic.

It is clear Mills made things happen, but before we leave today I would like to share just a few short snippets to show that he had other passions as well. It should be no surprise that he also devoted this same drive and energy to them.

Let’s start with Mills’ passion for horticulture. His garden was his great delight and in particular his orchard. His apples were his nightly treat – one description of him said that every night he studied until 11, ate a baked apple and retired. Students were often invited over for a glass of cider and felt it an honor to have been asked. He invented a cold storage system for his apples that was a marvel to all who saw it. This storage house assured a supply of fresh apples for cider well into the spring.

Mills was also passionate about books. He served as the college librarian for a number of years and his piece from the Wabash Magazine of 1871 is a stirring plea for support to fill the beautiful new Library space with books. That space was, incidentally, the ground floor of the north wing of Center Hall. We know it as the business office.

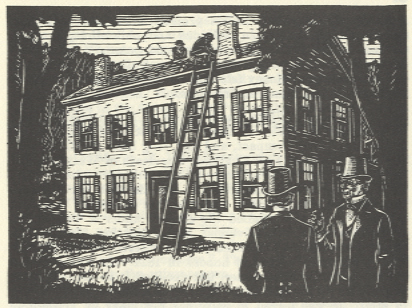

He was also a land developer. In 1850, years after the college abandoned the original site, and Forest Hall with it, Mills bought the parcel for $1,050. A great deal of the west end was at one time owned by Mills. To save the old building, he had Forest Hall taken apart and reassembled on his ground here – originally where the Sparks Center is now.

On another part of his land he created a cemetery for those members of the Wabash family, including his own infant children, who died early in our history. Long since removed, the graveyard was about where the Trippet Hall parking lot is now.

Marshall Street, just across from the Sigma Chi house, is named for his only son who survived into manhood. Marshall served in the Civil War, returned to finish at Wabash, died soon after, and was buried there. The entry to the cemetery was off of that short street.

When the college needed additional housing Caleb Mills fixed up Forest Hall as a dormitory. It had baths for the students, a pretty big deal at the time and a dining hall that could seat 50.

As he neared the end of his life, Mills gave Forest Hall to the College. So the fact that we have the building in which classes were first held is due to Caleb Mills. He bought it, saved it, moved it and made it useful to Wabash, thus ensuring its survival.

I started this by describing Mills as a man of action. Let me finish our look at Mills with one last story.

In his article on the history of Wabash for the December 1894 [p105] issue of the Wabash Magazine, long serving faculty member John Lyle Campbell described Edmund Hovey as a thoughtful down to Earth man. Mills, he said, was the creative, energetic man.

With this description in mind, from Wabash College, the First Hundred Years comes this story. In 1853 Hovey had reprimanded a student for card playing. At that time many activities were forbidden to students and gambling was high on the list, as was drinking. Both were considered quite serious offenses. So when Hovey got word that this same student was hosting a card party in his dormitory room, Hovey went to stop it. At this time the dormitory, South Hall, was set up rather like a suite today with a common room and two separate single bedrooms. When Hovey came in the students ran to the bedroom and locked the door. When Hovey tried to force it open he injured his knee. Mills was sent for and arrived on the scene with an axe. Never one to delay when action was needed, Mills took his axe and chopped open the door. The final report is that most of the fellows apologized for their behavior and were allowed to stay in college. The host, we are told, was unrepentant and defiant, then expelled.

Caleb Mills was a man of convictions, of faith and always a man of action. If he was passionate about a subject, then he acted on that. He was a man of action, always in motion. He was so much more than simply the first member of the faculty, or the owner of the famous bell. I hope you have enjoyed getting to know Caleb Mills, the activist. Thank you!

Beth Swift, Archivist, Wabash College