When I first received the Dill Fund award, I had a clear and comfortable plan. As an applied math and physics student, my project was supposed to be a direct application of a known mathematical concept to a physical scenario. Having spent the previous semester studying electrodynamics—a field known for using complex multivariable calculus and PDEs to describe the physical reality of electromagnetic fields—I was confident in my ability to work at the intersection of complex math and the real world. The initial goal was to take a tool called an “A-contraction” and apply it. It felt like familiar ground.

However, research rarely follows a straight path. As my mentor and I began to work with the mathematical framework of the A-contraction, we uncovered an issue. It wasn’t a problem with our application, but a subtle flaw within the mathematical theory itself. The tool was broken for the dislocated metric space we were trying to apply it to.. Suddenly, the entire course of my research shifted. I was no longer applying a concept; I was trying to fix one. This was a challenge I never imagined myself undertaking: diving deep into pure, abstract mathematics to repair a theoretical model. The most daunting part was that I hadn’t taken many of the prerequisite pure math classes usually needed for this kind of work. I was venturing into a completely unfamiliar territory.

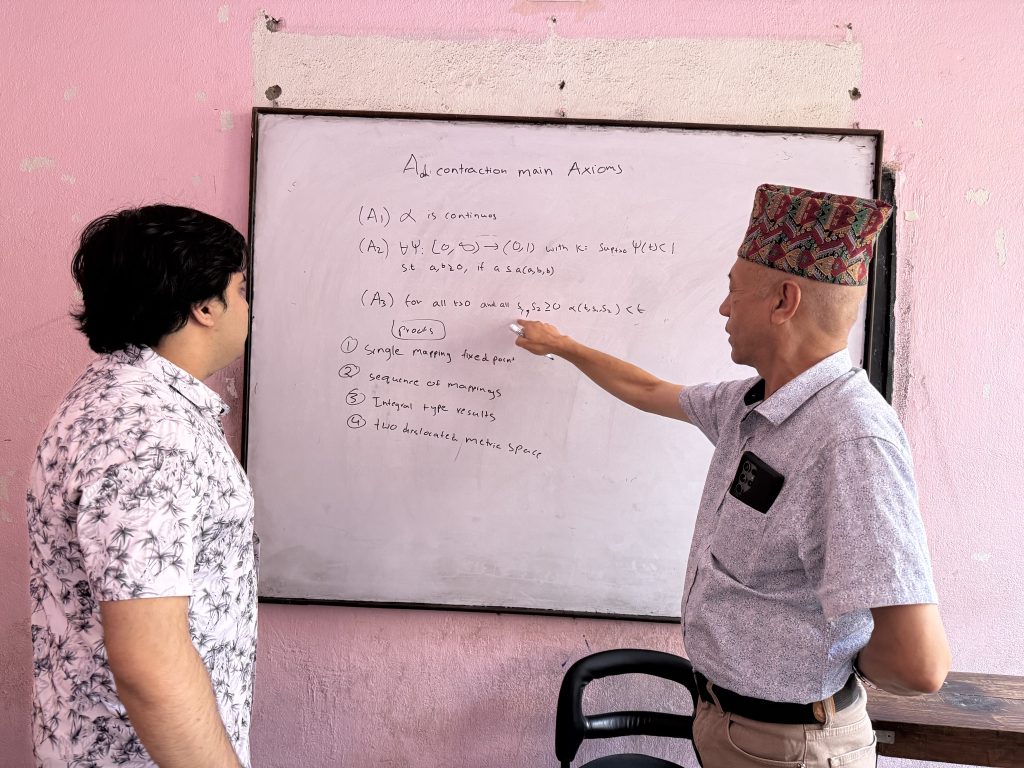

This is where the guidance of my mentor became the most critical part of my project. As a veteran in this field with years of experience developing new mathematical theorems, he patiently guided me through the complex proofs and abstract structures. He helped me build the intuition I was missing from my formal coursework.

While working late one day to structure our new model, I had a moment of connection. The abstract process reminded me of something I had done before, in a numerical analysis class I had taken with Dr. Westphal. In that class, we used fixed-point theorems for a very concrete task: numerical root finding. I realised that what I was doing now—developing what we would call an “Ad-contraction”—was a much more general and abstract version of that same core idea. That connection between a concrete application I knew and the abstract theory I was building was the key that unlocked my understanding.

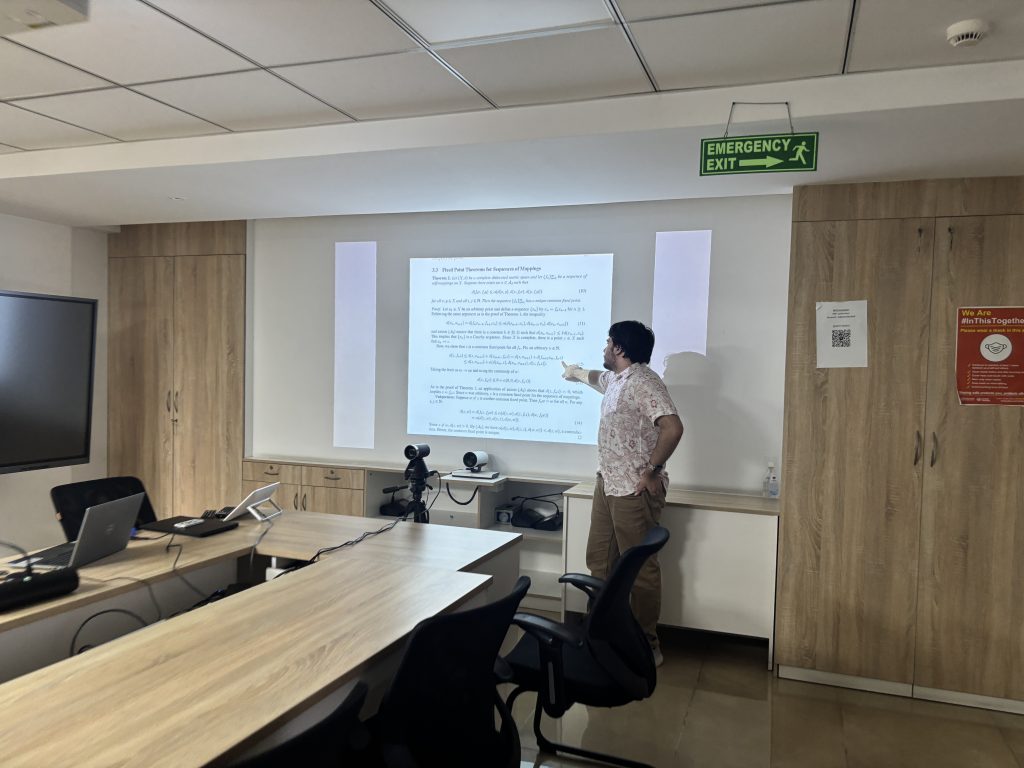

From there, we successfully developed our new model, which fixed the flaw in the original theory. This work led to a series of new fixed-point theorems and a paper that has now been submitted to a mathematics journal.

This experience, made possible by the Dill Fund, taught me more than I could have imagined. I experienced the adaptation and problem-solving required for successful research, especially when I was pushed outside my comfort zone. It showed me that even with a background in the application of math, I could contribute to fundamental, abstract theory.

I am incredibly grateful to the Dill Fund for this opportunity and to my mentor for his unwavering support. This project has solidified my confidence and has fundamentally shaped my desire to pursue a research career.

For those interested in the technical details, our pre-print paper is available on the arXiv preprint server: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2507.15635.