We entered the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews around 3 pm. The museum housed a millennium’s worth of Jewish narratives in Poland. During the Middle Ages, Poland emerged as a safe place for Jews although it was mostly Christian. Persecutions were common in other European countries, but King Casimir, whose reign from 1333 to 1380 was characterized by policies towards Jewish communities, stabilized the new tradition of tolerance and protection of Jews. For example, there was a fundamental law (Statue of Kalisz) that stated laws for Jews, such as “Neighbors are obliged to defend Jews against night assaults, under a fine of 30 shillings.”

Jews were allowed to settle in the borders and edges of cities and were given relative autonomy to manage their communities and practice their religion. This relative independence, however, came with a significant caveat: Jews were technically considered the “property” of dukes or the monarchy. Whilst this was seemingly derogatory, it ironically functioned as a protective shield against both external threats and local hostilities.

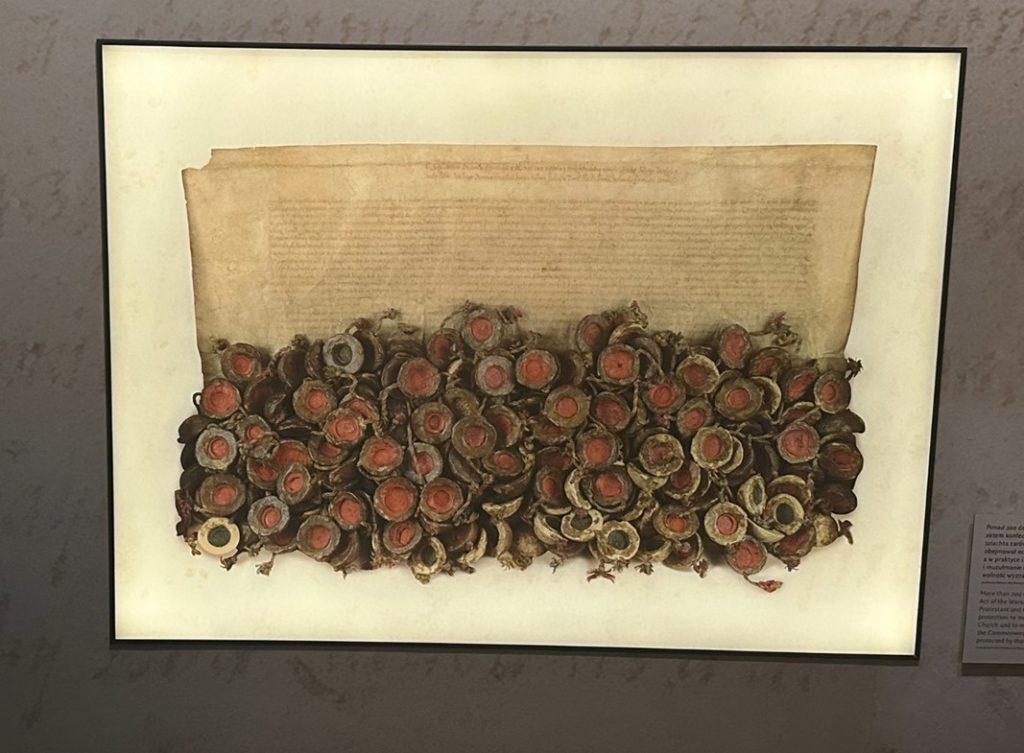

Additionally, the Act of the Warsaw Confederation was passed by the nobility at the Sejm in 1573. It stated, “that the pace be kept between people of different faith and liturgy.” Thus, as the most tolerant act of its kind in Europe, Poland was criticized not only as a “Jewish paradise” but also as a “haven for heretics.”

In my opinion, the progressive nature of this act shows there was early recognition of religious pluralism that was exceedingly rare for the time. It highlights how Poland, at various points in its history, served as a leader in cultivating an environment where diverse religious beliefs could coexist relatively peacefully.

In This Way to the Gas, Ladies, and Gentlemen, Borowski’s depiction of the Holocaust reflects the ultimate betrayal of the societal contract that once protected Jews but also highlights the fragility of tolerance in the face of radical ideologies. It helps structure the museum’s recounting of Jewish history—a continuum of hope, resilience, betrayal, and tragedy.

Furthermore, the museum does not shy away from the conflicts that arose from the coexistence. Jews remained vulnerable to the shifting whims of the monarchy and the local population. This precarious balance between autonomy and dependency is a recurring theme. Visiting this museum, I was able to learn deeply about Jews. Like our guide, Pawel told us we should view them as individuals who are similar to who we are instead of viewing them as people defined solely by the tragedies of the Holocaust.