With Veteran’s Day this week, I thought I might write a little piece about Wabash and the Student Army Training Corps. From an article in the Wabash College Record-Bulletin of October 1918 we have part of the story.

With Veteran’s Day this week, I thought I might write a little piece about Wabash and the Student Army Training Corps. From an article in the Wabash College Record-Bulletin of October 1918 we have part of the story.

“During the latter half of the last college year the steady decrease in the number of men students, bought about through war conditions, became so marked in the colleges and universities of the country as to create concern, not only among educators but among the military authorities as well. It became evident that there was great danger of depletion of our reserve of trained men for leadership in the long war then in prospect and in the peace which was hoped for…The most important points in this plan were:

“That military instruction under officers of the United States Army was to be provided in all institutions enrolling one hundred or more able-bodied students above the age of eighteen years.

“That enlistment in the training units thus formed should be voluntary, each student becoming, upon enlistment, a member of the Army of the United States and receiving from the government all necessary military equipment but no pay.

“That unless urgent necessity compelled it, no students were to be called into active service until they had reached the age of twenty-one. The aims of the proposed plan were stated to be to develop the large body of young men in the colleges as a great military asset and to prevent by the offer of an immediate military status to the student an unnecessary and wasteful depletion of the colleges through indiscriminate volunteering.”

As is often the case, events changed plans. The draft age was lowered and so the S.A.T.C. changed too. Students who were members of the SATC were to receive officer training and continue their academic studies. If needed by the Army, these men could be sent to officers’ training camps. There was one other change, these men were also to be paid at the rate of a private in the army AND their tuition and other college bills would be paid.

A statewide canvas was implemented to identify the young men in Indiana, “eligible for college entrance.” In addition the College was required to provide lodging and food, under contract with the War Department. A contract was signed in September of 1918 to provide room, board and an education to 400 men, referred to as “soldier-students.”

A space was cleared between South Hall [where Baxter Hall is now] and the new Gymnasium/Armory for the barracks. Here is one view of the barracks. In the back at left is South Hall.

Each building was to house 200 men and measured 215 x 42 feet with sidewalls of 11 feet and equipped with central heat. Bathing, laundry and other necessaries were housed in the building between the two long dorms. Here is a picture taken inside of one of the dorms.

Each building was to house 200 men and measured 215 x 42 feet with sidewalls of 11 feet and equipped with central heat. Bathing, laundry and other necessaries were housed in the building between the two long dorms. Here is a picture taken inside of one of the dorms.

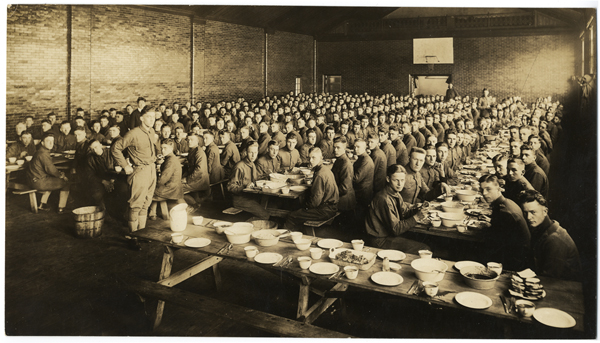

To feed all of these fellows a mess hall was established in the second floor of the Armory. This marks the first time that Wabash, as a college, fed its students. Here is a picture of that mess hall and all of the SATC fellows. This space was designed as an auxiliary gymnasium, note the basketball goal in the rear of the room.

With all systems nearly ready the big day for the opening of the Student Army Training Corps approached. All SATC programs across the nation were synchronized such that all swearing in ceremonies occurred simultaneously. Here is a picture of that ceremony on the Wabash campus. This picture was taken in the Arboretum near Wabash Avenue.

In the Wabash College Record-Bulletin narrative of the SATC, it notes that about half of the student body of 525 were inducted into the U.S. Army. It adds, “Further inductions were prevented by lack of sufficient induction blanks, the arrival of which from Washington was delayed for several weeks. The inducted men were quartered in the completed barracks, and the other students occupied their lodgings in town while awaiting induction.”

Above is a photograph of the entire Corps at drill. The uniforms had yet to arrive. But the soldier-students were at work, as was the band. Here is an image of the SATC band marching on the field.

Above is a photograph of the entire Corps at drill. The uniforms had yet to arrive. But the soldier-students were at work, as was the band. Here is an image of the SATC band marching on the field.

Classes had just started when they were cancelled on account of the deadly influenza epidemic. It hit Wabash on Monday, October 7, 1918 when six men appeared at sick call with high fevers, by that night 11 more were added. All sick call fellows were taken to the Phi Delta Theta fraternity on the corner of College and Jefferson. The fraternity house was set up as an infirmary, with a capacity of six patients. All students who were not a part of the SATC were sent home until Wabash reopened. Those in the SATC stayed on campus and the flu hit them hard. The day before the Infirmary was to open there were 17 men in need of care and within the week, there were 84 students in the hospital. Here is a picture of the Phi Delt house as it was at that time.

A total of 120 cases were received at the infirmary and no students died. This is credited to the superior nursing staff. From the college history, The First Hundred Years comes this excerpt, “College and town were very proud of this record. It was attained only by an outpouring of energy nothing short of heroic. Miss Mary Jolley, of Crawfordsville, Head Nurse, remained steadily at her post in spite of the fact that she herself was attacked by influenza. Volunteers stepped forward to help her. Three of these volunteers were trained nurses – Miss May Huston, Miss Edith Hunt and Miss Ethel Newell.” Many other ladies from the town helped out too. Miss Newell, one of the nurses, had recently had pneumonia, yet volunteered anyway. Her illness returned and she died – the only casualty of the Wabash outbreak.

A total of 120 cases were received at the infirmary and no students died. This is credited to the superior nursing staff. From the college history, The First Hundred Years comes this excerpt, “College and town were very proud of this record. It was attained only by an outpouring of energy nothing short of heroic. Miss Mary Jolley, of Crawfordsville, Head Nurse, remained steadily at her post in spite of the fact that she herself was attacked by influenza. Volunteers stepped forward to help her. Three of these volunteers were trained nurses – Miss May Huston, Miss Edith Hunt and Miss Ethel Newell.” Many other ladies from the town helped out too. Miss Newell, one of the nurses, had recently had pneumonia, yet volunteered anyway. Her illness returned and she died – the only casualty of the Wabash outbreak.

By October 24, the outbreak had run its course and classes resumed. Again, from the Record-Bulletin we learn that the remaining induction blanks had arrived and the remainder of the SATC men were inducted, bringing the total at Wabash to 400 men. In just a few days, the Great War ended with the signing of the Armistice on November 11, 1918. The SATC men were mustered out, though many of them stayed at Wabash and completed their studies. A good thing too, as one of these fellows is credited with creating mass production techniques for Alexander Fleming’s penicillin work. More about Andrew J. Moyer may be found here:

http://indianapublicmedia.org/momentofindianahistory/saving-lives-grand-scale/

Beth Swift

Archivist

Wabash College